Barrister wigs, Mafia bosses, and accents that range from Little Italy to Little Odessa – I review some of my favorite crime and mystery audiobooks for Crime Reads. Read the full article here.

Writers Read

I recently wrote a guest post for Writers Read about the books I’m currently nose-to-page with. To see the full list, and to learn why these titles left such an impression on me, click here.

That Nice Richard II

I’ve been reading Shakespeare’s kings, starting with Richard II. Did you know that when Bolingbroke was banished, his children came under “royal protection?” So his sons were essentially Richard’s hostages. When Richard went to Ireland in 1399 as everything was unravelling for him, he took Henry, aged 12, (future Henry V) and Humphrey of Gloucester, aged 9, with him, and left them at Castle Trim “under ward” while he went home to negotiate with their father. Princes in towers. Trim was the northernmost stronghold of the English Pale, and at least when we were there in March, while impressive, it is plenty grim. I’ve always sort of loved Richard II (“Down, down I come like glistering Phaeton!”) but now I’m beginning to wish I wrote historical fiction. Young Hal, of the taverns but also, though Shakespeare doesn’t mention it, a hero of battlefields in Wales and elsewhere from the time he was thirteen, had to have had very complicated feelings about poetic Uncle Richard. At least Richard didn’t kill them, but would you leave your beloved little cousins here?

The rooks above the keep, which you can see in the sky, are upset because there was a small falcon, we think a kestrel, up to no good there that afternoon. She was beautiful but she kept the locals busy.

I know someone gave it to you over the holidays…

I know someone gave it to you over the holidays. I know you know that everyone else loved it but you got stuck in the Las Vegas part. So many books, so little time. I sympathize totally, but keep going; it’s really really worth it.

The reviewers all invoke Dickens, and that is both completely right and quite misleading. If you love Dickens, at first you feel hard done by, because Dickens is almost always funny, and The Goldfinch isn’t. There are other things in life. Dickens is also almost always sentimental and melodramatic, because he was working in a century when popular entertainment had to be made of BIG gestures so they could be seen and heard in the back of the stalls, in huge unamplified theaters. We live in a world where the images are so big on the movie screen, or so close to us in the home tube, that in our storytelling, anything other than tiny natural gestures, movements of the eyes, post-Method acting, feels crude and silly. And yet we have the same hunger for narrative, for the big sweeping story, that we have always had. Tartt has given us a truly Dickensian plot and characters, with all the pleasure that implies, in the only way she could for a 21st century audience: with meticulously- observed details of how we act now, and who we are now. She makes us feel that this marvelous story could really be unfolding over there in the Village, on that street you walked down yesterday.

You’ve got to get over feeling that if it’s Dickensian, it should read like Dickens. And accept that the Las Vegas part is absolutely necessary. I could say more, about how just as you recognize Great Expectations, she knows you’ve caught on to that and … to say more would be to say too much. Really, go back and finish it; it’s heaven.

Books I loved in 2013 (but first, a rebellion)

For years, I’ve kept a private log of books read for research or pleasure. In 2013, I decided to try keeping this log in public, on a certain website I won’t name, thinking it might be interesting and fun to share reading lists with friends. It wasn’t.

About a minute after I undertook this experiment, the site was bought by another entity I won’t name, one widely understood to be engaged in crushing publishing as we know it, not to mention dissolving the vital link between writers and readers whereby editors, critics and reviewers with known credentials bring a professional standard to surveying what has been published and alerting the rest of us to what might deserve our attention or reward our investments of time and lucre. Crowd-sourced ratings of washing machines and electric curling irons make sense. The things worked or they didn’t; they broke or they didn’t. Crowd-sourced reviews of books, especially when they crowd out professional signed reviews, are changing the world for readers, and not for the better.

To state only one reason I abandoned the readers’ website: I don’t see how it helps anyone to rate books from one to five stars. If you give five stars to a book that totally succeeds as a diversion, what do you do with a book that totally succeeds as a masterpiece? And if we’re friends and you give three stars to something I think is a masterpiece, or five to something I didn’t admire, how does that help anyone except the people tracking our tastes in order to try to sell us things?

Not changing the subject: a grateful word here about the Times (of London) Literary Supplement, a weekly review still devoted entirely to books, deeper and wider in its interests than what local alternatives remain. In late November the TLS offers Books of the Year, not the Ten Best, or Fifty Best (almost as questionable an undertaking as rating books from one to five). Instead they ask about seventy scholars, poets, novelists, critics, historians, classicists, musicologists and so on to name the new book or books that had meant most to them. Each contributor has a couple of hundred words in which to describe one or two treasured titles. Sometimes the books are for generalists but some are wonderfully arcane, and the whole enterprise is absolutely fascinating. When a book turns up on multiple lists – that was the way many of us discovered The Hare with Amber Eyes for instance– you take notice. In the spirit of the TLS, here without stars but with thanks for a year of pleasures, are some of the books I would recommend if you had stopped up for coffee.

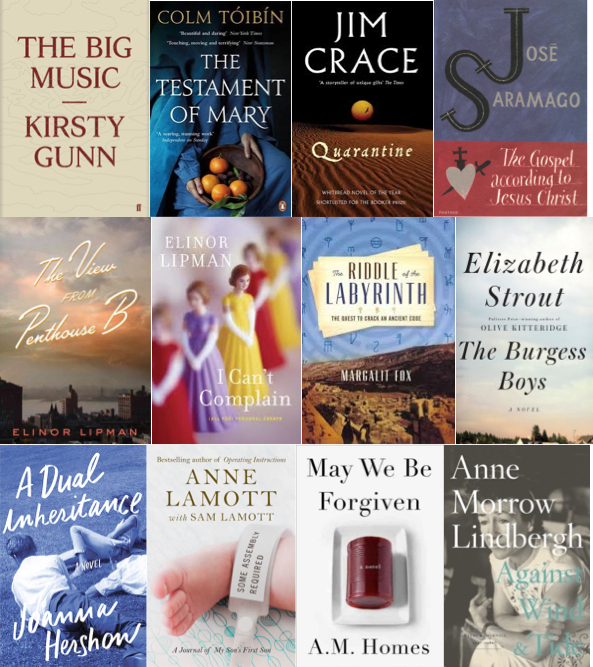

Last year the multiply- mentioned book on the TLS list that most called to me was The Big Music by Kirsty Gunn, a novel masquerading as a work of scholarship about a family of famous pipers in the Scottish Highlands, but which is in fact a brilliantly structured (the story takes the shape of the music described) and beautifully written saga or elegy or both. It looks immense but is less daunting once you realize the footnotes are window dressing.

The Testament of Mary, by Colm Toibin. What a brilliant idea, the gospel story as seen by the subject’s very human mother. We’ve heard that narrative from everyone else’s point of view, it seems. Toibin has written often of mothers and sons, but never so searingly. At a PEN Author Evening dinner in New York we had the good fortune to hear him talk about it. Asked what he had read to prepare to write Testament, Toibin mentioned Quarantine, by Jim Crace, and The Gospel According to Jesus Christ by Jose Saramago. Off to the bookstore.

Quarantine, by the author of the strange and wonderful Being Dead, is a provocative account of the forty days in the desert. It’s uncomfortable, with the most gut-twisting portrayal of Satan ever, and unforgettable.

But the Saramago! This was the second year in a row that the honored author at a PEN dinner had named a Saramago book as his idea of what to read – last year it was Billy Collins and Blindness. For some reason I’m one of three people in the world who didn’t take to Blindness, but The Gospel is the book that put paid for me to any thought that you can rate books on a scale of one to five. On a scale of one to five, for me it’s about a twelve.

The View From Penthouse B. No one living does what Elinor Lipman does, so sweetly, wittily and reliably does she create worlds in which the right people find love, the right people are balked, no planes crash, (I read it on a plane and I’m a nervous traveler) and if you’re not smiling from page one, you’re laughing outright. Only P.G. Wodehouse consistently delivers that kind of pleasure. I loved I Can’t Complain, her collection of (all too personal) essays, as well.

The Riddle of the Labyrinth, The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code, by Margalit Fox. In 1900, searching for answers to the many mysteries surrounding the Mycenean cultures of Aegean, a British archeologist working on Crete found Bronze Age clay writing tablets that had accidentally been fired when the palace that housed them burned down. The palace is now thought to have been the seat of King Minos, he of the labyrinth and the Minotaur. (Note to self: time to reread Mary Renault.) No one knew what kind of script it was on the tablets, hieroglyph, alphabet or syllabary, and no one knew what language was being written, and nothing like a Rosetta stone was ever found. And yet the script, called Linear B, has been decoded. The story of how, and by whom, and who got the credit is so fascinating and so well-told by Fox that I still can’t shut up about it.

Elizabeth Strout is a giant. Her Olive Kittredge won the Pulitzer in 2009, and her lovely Abide with Me should be read by anyone who admired Marilyn Robinson’s Gilead, and by everybody else. The Burgess Boys was a favorite book of the summer.

A Dual Inheritance by Joanna Hershon is delicious, beautifully executed, and satisfying in every way. It’s a sharp, smart, insightful, very American tale of two families, the kind of book that you disappear into for hours, and think about for months after it’s done.

I’m a huge fan of Annie Lamott’s writings on life, on faith, and on writing, but for some reason I resisted Some Assembly Required, a Journal of My Son’s First Son. Well, I know the reason; I feared it was just some publisher’s good idea, to get her to try to repeat the success she’d had with Operating Instructions, her account of raising her son. It probably was such an idea in the beginning, but a very very good idea it was. The book is wise and funny, and interesting and human, and I kick myself that I waited so long to enjoy it.

Ditto May We Be Forgiven, by A.M. Homes. I bought it when it came out but then lost it in a pile of research reading. It’s a miracle when a writer can be this hilarious while being darkly serious about the state of the national soul. There’s a moment in which the teenage niece and ward of the (childless male) narrator calls for urgently-needed advice of an intimate kind he is spectacularly ill-equipped to give; that scene alone has decided me to shelve this book beside the Evelyn Waughs.

Somewhere in there I finally allowed myself to get to the end of Against Wind and Tide, letters and journals and the last writings we will have from Anne Morrow Lindbergh. I made it last as long as I could. What a woman, what a writer. What grace, what a life.